BoE: Understanding the central bank's balance sheet

Role of the central bank balance sheet

1. Ultimate means of settlement: One of the interesting features of the central bank's balance sheet is that its main liabilities are banknotes and commercial bank reserves, which are a form of money in the modern economy. Money is a form of IOU which allows agents to settle transactions. Agents should always be willing to accept money, as both a store of value and a unit of account, as long as they trust the issuer of money.

While the banknotes play an important role in transactions, in most economies they do not make up the majority of money by value. Instead, commercial bank deposits form the majority of the money value. These balances are held by economic agents such as commercial banks and can be transferred electronically between depositors. The confidence in this type of money depends on the trust of people in the commercial bank where they hold the deposit.

In most cases balances held in commercial banks are exchangeable on demand for banknotes; this guarantee of direct convertibility into a form of central bank liability provides some degree of trust in the value of such money. When the commercial banks need to settle transactions between economic agents by transferring balances between themselves and other commercial banks, they need the central bank. In such cases, reserves move across the balance sheet of the central bank with one commercial bank's reserve account being debited and another being credited. One the other hand, if a transaction moves money between the agents that hold bank accounts at the same bank, then the central bank is not required, merely credit and debit of different accounts are all that happens.

So, the central bank provides a transactional means that underpins confidence in commercial banks deposits as a means of settlement. In this way, it also facilitates banks to create money through credit creation.

Recent changes in central bank balance sheets

1. Price versus quantity targets: In the late 1970s and early 1980s academic ideas of having the central bank target specific narrow measures of money as operational target led to greater interest in the central bank's balance sheet. However, the relatively poor performance of such operational targets through the 1980s led to many central banks abandoning such quantitative targets, and they moved towards targeting the price of money. The central banks set inflation or a similar target and used the short-term interbank interest rate as the operational target of monetary policy.

2. Crisis response and unconventional monetary policy: The initial stage of the crisis saw a stagnation of the financial markets across the globe. The interbank markets froze due to fears of counterparty credit and self-sustainability. The central banks responded by increasing the supply of reserves through various methods. In the early stages of the crisis, the central bank increased the liabilities and pumped in liquidity into the system, known as a liability-driven method.

Once the price targets had reached their effective lower bounds, central banks implemented policies of asset purchases to lower long term interest rates. These asset purchases were financed by the creation of reserves, known as asset driven approach.

Components of the balance sheets

Liabilities

1. Liabilities - Banknotes: This element covers banknotes issued by the central bank that are in circulation. The process involves commercial banks drawing down banknotes in exchange for reserve balances held at the central bank. People can then obtain banknotes through direct withdrawals through banks. Short-term demand for banknotes is often volatile and liked to seasonal factors as well. In the long run, though, banknote demand has been linked to growth in nominal GDP. Other factors which influence its long-run demand is the opportunity cost of holding cash (for example in the period of low-interest rate the opportunity cost of holding cost is low), confidence in central banks, size of informal economy and payment technology.

2. Liabilities - Commercial bank reserves: Reserves are overnight balances that banks held by commercial banks at the central bank in the same way that individuals hold such accounts at commercial banks. Along with the banknotes, reserves are the most liquid, risk-free asset in the economy.

3. Misconceptions regarding reserves:

(a) Reserves and other assets: One of the biggest misconceptions is the idea that commercial banks in aggregate can choose between reserves and other assets. Individual banks can choose between reserves and other assets, at the system-wide level the quantity of reserves in the central bank's balance sheet doesn't change. The following figure shows when an individual bank attempts to reduce its reserve balance by buying assets. What can be observed is that although at the individual level the reserves and assets change, at system-wide level overall reserves do not change, in this case, they just transfer from Bank A to Bank B.

(d) Required reserves for revenue purposes: Reserve requirements can also be used for the central bank's revenue purposes. In the UK, commercial banks over a certain size are required to hold a small unremunerated balance at the BoE, known as Cash Ratio Deposits, the amount is then invested by BoE to earn revenue.

(e) Required reserves for sectorial behavioural purposes: It can be used by central banks to try to influence commercial bank behaviour towards different sectors of the economy.

5. Voluntary versus excess free reserves: In addition to required reserves commercial banks may also hold free reserves at the central bank. Free reserves are any reserves that do not contribute to the fulfilment of reserve requirements. Free reserves can be further broken down into two categories: voluntary free reserves, which commercial banks are happy to hold, and excess free reserves, which commercial banks do not wish to hold and will look to trade away.

In developed economies, free reserves are relatively time-invariant. In developing economies, however, free reserves can be significant and reflect the consequences of actions undertaken by the central bank.

Capital

1. Liabilities - Capital: Like private sector institutions central banks carry capital on their balance sheet and like private institutions the capital buffer becomes the channel through which the central bank absorbs losses. Unlike private institutions, central banks are not subject to regulatory capital requirements. Also, if a private company wishes to increase the amount of capital it can do so by retaining the earnings, however, the ability of central banks to do this is quite limited.

(a) The optimal level of capital in central banks: The correct level of capital for a specific central bank will be determined by a number of unique factors related to the situation it faces. These include its institutional structure and the types of operations it faces. What should be remembered is that unlike private institutions, the aim of central banks is to achieve policy target and not profits. Therefore, sometimes it may face a situation when it's socially optimal to lose money or take greater risks.

Assets

1. Assets - Foreign assets: Foreign assets (and liabilities) are those denominated in the non-domestic currency. The main form of foreign assets held by central banks is foreign exchange reserves. To counter an appreciation of the domestic currency, for example, the central bank will intervene by selling domestic assets in exchange for foreign currency denominated assets. This increases the supply of domestic currency and increases demand for foreign currency assets, which should offset the appreciation pressure.

The scale of foreign exchange reserves held by the central banks will likely be proportional to the scale of foreign exchange intervention. Foreign exchange reserves are often held in very liquid and safe assets, such as developed economy cash and government bonds. In many economies where there is significant forex activity, but underdeveloped financial markets, the central bank may provide foreign currency facilities to its commercial banks. But to carry this function, which would create foreign currency liabilities, the central bank needs to match it by either existing holdings of foreign currency assets or an agreed swap line.

1. Assets - Government balances: Central bank also acts as a banker to the government. Where government deposits funds at the central bank these appear as liabilities. So, when the government increases its balance at the central bank, through collecting taxes or issuing debt, it does so at the expense of the balances of commercial banks; when it reduces its balance, through expenditure or paying salaries, it does so by increasing the reserves available to commercial banks.

Central Bank Operations

As the majority of changes in the elements of the central bank's balance sheet are exogenous, the central bank requires some mechanisms to respond to these changes to ensure that the optimal quantity of reserves is available to the banking system. It is through central bank operations that the central bank controls the availability of reserves to the system.

(a) Types of central bank operation: Operations to supply liquidity to the market include both active (open market operations) and passive (standing facilities) operations. Active operations can be thought of as operations that are: open to a wide range of counterparties; initiated by the central bank; and settled through an open auction mechanism. On the other hand, passive operations can be thought of operations that are conducted bilaterally between the commercial bank and the central bank at the initiation of the commercial bank. Central banks can also choose to operate across a range of maturities.

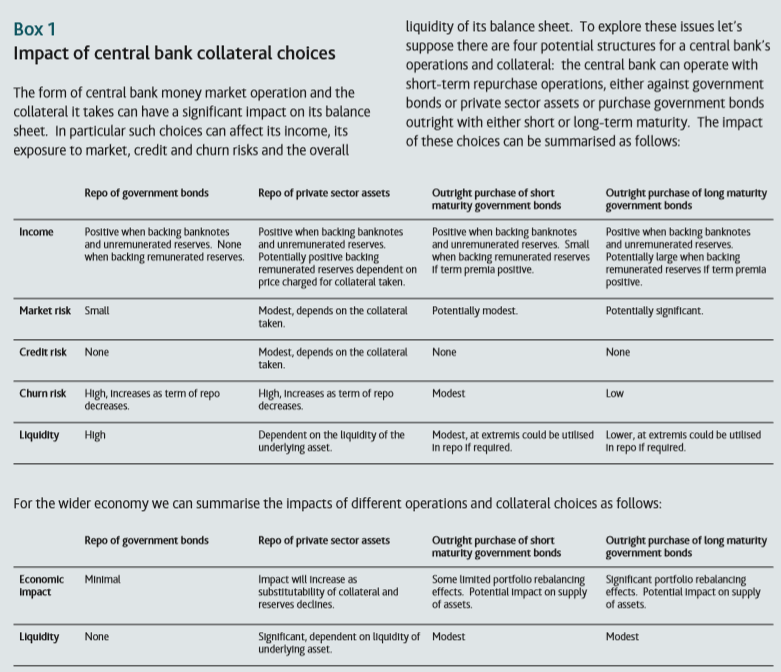

(b) Collateral: From a balance sheet perspective, when a central bank lends to a commercial bank it creates a fresh asset. This asset is the collateral taken from the bank, to protect the central bank against the possibility of loss resulting from credit and market risk. Collateral choice impacts central banks income, credit and market risks, while for the wider economy these choices have both a portfolio balance and liquidity impact.

Changes in central bank balance sheets

1. Ultimate means of settlement: One of the interesting features of the central bank's balance sheet is that its main liabilities are banknotes and commercial bank reserves, which are a form of money in the modern economy. Money is a form of IOU which allows agents to settle transactions. Agents should always be willing to accept money, as both a store of value and a unit of account, as long as they trust the issuer of money.

While the banknotes play an important role in transactions, in most economies they do not make up the majority of money by value. Instead, commercial bank deposits form the majority of the money value. These balances are held by economic agents such as commercial banks and can be transferred electronically between depositors. The confidence in this type of money depends on the trust of people in the commercial bank where they hold the deposit.

In most cases balances held in commercial banks are exchangeable on demand for banknotes; this guarantee of direct convertibility into a form of central bank liability provides some degree of trust in the value of such money. When the commercial banks need to settle transactions between economic agents by transferring balances between themselves and other commercial banks, they need the central bank. In such cases, reserves move across the balance sheet of the central bank with one commercial bank's reserve account being debited and another being credited. One the other hand, if a transaction moves money between the agents that hold bank accounts at the same bank, then the central bank is not required, merely credit and debit of different accounts are all that happens.

So, the central bank provides a transactional means that underpins confidence in commercial banks deposits as a means of settlement. In this way, it also facilitates banks to create money through credit creation.

Recent changes in central bank balance sheets

1. Price versus quantity targets: In the late 1970s and early 1980s academic ideas of having the central bank target specific narrow measures of money as operational target led to greater interest in the central bank's balance sheet. However, the relatively poor performance of such operational targets through the 1980s led to many central banks abandoning such quantitative targets, and they moved towards targeting the price of money. The central banks set inflation or a similar target and used the short-term interbank interest rate as the operational target of monetary policy.

2. Crisis response and unconventional monetary policy: The initial stage of the crisis saw a stagnation of the financial markets across the globe. The interbank markets froze due to fears of counterparty credit and self-sustainability. The central banks responded by increasing the supply of reserves through various methods. In the early stages of the crisis, the central bank increased the liabilities and pumped in liquidity into the system, known as a liability-driven method.

Once the price targets had reached their effective lower bounds, central banks implemented policies of asset purchases to lower long term interest rates. These asset purchases were financed by the creation of reserves, known as asset driven approach.

Components of the balance sheets

Liabilities

1. Liabilities - Banknotes: This element covers banknotes issued by the central bank that are in circulation. The process involves commercial banks drawing down banknotes in exchange for reserve balances held at the central bank. People can then obtain banknotes through direct withdrawals through banks. Short-term demand for banknotes is often volatile and liked to seasonal factors as well. In the long run, though, banknote demand has been linked to growth in nominal GDP. Other factors which influence its long-run demand is the opportunity cost of holding cash (for example in the period of low-interest rate the opportunity cost of holding cost is low), confidence in central banks, size of informal economy and payment technology.

2. Liabilities - Commercial bank reserves: Reserves are overnight balances that banks held by commercial banks at the central bank in the same way that individuals hold such accounts at commercial banks. Along with the banknotes, reserves are the most liquid, risk-free asset in the economy.

3. Misconceptions regarding reserves:

(a) Reserves and other assets: One of the biggest misconceptions is the idea that commercial banks in aggregate can choose between reserves and other assets. Individual banks can choose between reserves and other assets, at the system-wide level the quantity of reserves in the central bank's balance sheet doesn't change. The following figure shows when an individual bank attempts to reduce its reserve balance by buying assets. What can be observed is that although at the individual level the reserves and assets change, at system-wide level overall reserves do not change, in this case, they just transfer from Bank A to Bank B.

Even when commercial banks increase their lending they cannot reduce the total amount of reserves in the system. The initial process of lending involves increasing the individual bank's balance sheet by adding loans (asset) and deposits (liabilities). At this point there is no impact on the quantity of reserves, they only change when the recipient of the loans spends it, in which case it would move between commercial banks as shown.

(b) Reserves to lend: Another misconception is that commercial banks require reserves to lend. As we discussed above, the process of creating a new loan by a commercial bank does not immediately impact on the reserve quantity in the system. Only when the freshly created deposit is transferred between the commercial banks, the reserves need to move. So, when the central bank imposes reserve requirements, and there are no free reserves in the system, the lending by commercial banks would be affected. This explanation supports the traditional money multiplier explanation of the monetary policy.

Around 80% of the central banks impose reserve restrictions in a lagged manner. This means that current reserve requirements are imposed on lending measured in a previous period. Also, to achieve policy goals, most central banks ensure enough liquidity in the system. Therefore, while many things determine commercial bank lending, the availability of reserves is unlikely to be one of them. Commercial banks lend only if it is possible for them to do so, that is, when the return on the loan is greater than the cost of funding (that is, the market interest controlled by the central bank). Increased reserve levels impact lending only to the extent that if the central bank is unable to control conditions in the interbank market, then excess reserves push market rates lower and hence make more lending profitable. In addition to the market interest rate, the commercial bank also faces credit and liquidity risk premia. The size of such premia will be influenced by both macro factors and idiosyncratic factors. In addition to these, other factors such as regulatory and capital requirements, administrative and hedging costs, creditworthiness also determine the cost of lending by the banks.

4. Required versus free reserves: Many central banks impose reserve requirements on commercial banks that hold reserve accounts with them. Today there are five roles for reserve requirements: monetary policy purposes, liquidity management purposes, structural liquidity purposes, revenue purposes and sectorial behaviour purposes.

(a) Required reserves for monetary policy purposes: Required reserves can be employed for monetary policy if the reserves obtain interest at a rate below the market rate. Forcing commercial banks to hold reserve that pays a return below the prevailing market rate creates a deadweight loss on commercial bank lending. Varying the size of this deadweight loss will affect both lending and deposit rates offered by commercial banks. Thus, the impact of a change in reserve requirements has an economic effect equivalent to a change in interest rates.

Central banks use reserve requirements as monetary policy tools in countries which face inflationary pressures due to capital inflows. The resurgence in reserve requirements has also led to a greater examination of the mechanism through which they impact bank lending.

(b) Required reserves for liquidity management: To provide liquidity management role, reserves can be remunerated or unremunerated. If the reserves receive interest in line with prevailing market interest rates then the size of requirement does not play a direct monetary policy role, this is because whether keep the reserves in the central bank or lend it in interbank, the benefits would be the same. However, varying the size of the reserve requirement does however, impact the availability of collateral to the market if the central bank is providing such reserves to the market through collateralized operations.

(c) Required reserves for structural liquidity purposes: The variation of reserve requirements can be used by the central bank to change the desired liquidity shortage.

(d) Required reserves for revenue purposes: Reserve requirements can also be used for the central bank's revenue purposes. In the UK, commercial banks over a certain size are required to hold a small unremunerated balance at the BoE, known as Cash Ratio Deposits, the amount is then invested by BoE to earn revenue.

(e) Required reserves for sectorial behavioural purposes: It can be used by central banks to try to influence commercial bank behaviour towards different sectors of the economy.

5. Voluntary versus excess free reserves: In addition to required reserves commercial banks may also hold free reserves at the central bank. Free reserves are any reserves that do not contribute to the fulfilment of reserve requirements. Free reserves can be further broken down into two categories: voluntary free reserves, which commercial banks are happy to hold, and excess free reserves, which commercial banks do not wish to hold and will look to trade away.

In developed economies, free reserves are relatively time-invariant. In developing economies, however, free reserves can be significant and reflect the consequences of actions undertaken by the central bank.

Capital

1. Liabilities - Capital: Like private sector institutions central banks carry capital on their balance sheet and like private institutions the capital buffer becomes the channel through which the central bank absorbs losses. Unlike private institutions, central banks are not subject to regulatory capital requirements. Also, if a private company wishes to increase the amount of capital it can do so by retaining the earnings, however, the ability of central banks to do this is quite limited.

(a) The optimal level of capital in central banks: The correct level of capital for a specific central bank will be determined by a number of unique factors related to the situation it faces. These include its institutional structure and the types of operations it faces. What should be remembered is that unlike private institutions, the aim of central banks is to achieve policy target and not profits. Therefore, sometimes it may face a situation when it's socially optimal to lose money or take greater risks.

Assets

1. Assets - Foreign assets: Foreign assets (and liabilities) are those denominated in the non-domestic currency. The main form of foreign assets held by central banks is foreign exchange reserves. To counter an appreciation of the domestic currency, for example, the central bank will intervene by selling domestic assets in exchange for foreign currency denominated assets. This increases the supply of domestic currency and increases demand for foreign currency assets, which should offset the appreciation pressure.

The scale of foreign exchange reserves held by the central banks will likely be proportional to the scale of foreign exchange intervention. Foreign exchange reserves are often held in very liquid and safe assets, such as developed economy cash and government bonds. In many economies where there is significant forex activity, but underdeveloped financial markets, the central bank may provide foreign currency facilities to its commercial banks. But to carry this function, which would create foreign currency liabilities, the central bank needs to match it by either existing holdings of foreign currency assets or an agreed swap line.

1. Assets - Government balances: Central bank also acts as a banker to the government. Where government deposits funds at the central bank these appear as liabilities. So, when the government increases its balance at the central bank, through collecting taxes or issuing debt, it does so at the expense of the balances of commercial banks; when it reduces its balance, through expenditure or paying salaries, it does so by increasing the reserves available to commercial banks.

Central Bank Operations

As the majority of changes in the elements of the central bank's balance sheet are exogenous, the central bank requires some mechanisms to respond to these changes to ensure that the optimal quantity of reserves is available to the banking system. It is through central bank operations that the central bank controls the availability of reserves to the system.

(a) Types of central bank operation: Operations to supply liquidity to the market include both active (open market operations) and passive (standing facilities) operations. Active operations can be thought of as operations that are: open to a wide range of counterparties; initiated by the central bank; and settled through an open auction mechanism. On the other hand, passive operations can be thought of operations that are conducted bilaterally between the commercial bank and the central bank at the initiation of the commercial bank. Central banks can also choose to operate across a range of maturities.

(b) Collateral: From a balance sheet perspective, when a central bank lends to a commercial bank it creates a fresh asset. This asset is the collateral taken from the bank, to protect the central bank against the possibility of loss resulting from credit and market risk. Collateral choice impacts central banks income, credit and market risks, while for the wider economy these choices have both a portfolio balance and liquidity impact.

Changes in central bank balance sheets

(a) Asset versus liability-driven: A key determinant of how a central bank's balance sheet changes through time are whether growth in the balance sheet is driven by the assets or the liabilities.

A liability-driven central bank balance sheet grows through time as demand for central bank liabilities increases. With the growth in demand for central banks liabilities, the central bank, to ensure payments are made and operational targets are met, must respond by supplying required reserves through operations. Such a situation is referred to as a shortage of liquidity and is characterised by the majority of operations on the liability side.

On the other hand, an asset driven balance will grow as a result of policy decisions made regarding the asset side of the balance. Growth in any of the asset class exceeds demand for central banks liabilities, which create surplus liquidity. Two most common causes of surplus liquidity are growth in foreign assets and lending to the government.

(b) Impact of a surplus: Whether or not there is a surplus or a shortage of liquidity has implications for the central bank and has the potential to influence the following: (i) the transmission mechanism of monetary policy (ii) the conduct of central bank intervention in the money market (iii) the central bank's income.

When there is a shortage of liquidity, commercial banks are forced to borrow from the central bank, as a result, when the central bank is lending money to commercial banks it is able to choose the terms on which it deals, such as the assets it takes to match its liabilities. In these circumstances, operations should earn central banks money.

When there is a surplus of liquidity, then depending on the overall size of the surplus commercial banks may need to transact with the central bank in order to meet reserve requirements and make interbank payments. The central bank, therefore, maybe in a weaker position to dictate the terms on which it transacts with the market. In this situation, operations can cost the central bank money.

When there is a shortage of liquidity, therefore, the central bank will always lend enough to the market to obtain balance, but when there is a surplus of liquidity it is harder for the central bank to drain enough to obtain balance. In many cases of surplus liquidity, the central bank has less control over the first step of the monetary transmission mechanism.

(c) Policy regimes: Under inflation targeting or closely related policies, the central bank's main policy instrument is a short-term interest rate. To attain this, the central bank uses a combination of central bank operations and reserve requirements. If the central bank allows its exchange rate to float freely (no addition to the forex asset side) and does not engage in the monetisation of government (no addition of govt assets), then the central bank balance sheet will be characterized by a shortage of liquidity. The success of the central bank in achieving its inflation goals can be seen by the pace of growth in the balance sheet.

If the central bank instead targets the exchange rate then its balance sheets will be characterized by significant holdings of foreign assets. In such cases, the size of the central bank's assets exceeds the demand for domestic liabilities and systems are characterised by a surplus of liquidity. The scale of such reserves has led to many of these central banks facing a surplus of liquidity.

Comments

Post a Comment